The Anatomy of Knowing: Unpacking the Layers of Epistemology

Epistemology, the philosophical study of knowledge, explores the nature, scope, and limits of human understanding. It is concerned with questions like what knowledge is, how it is acquired, and how we can be certain of what we know. For those of you who are familiar with the IB, you will know it as TOK (Theory of Knowledge). However, it goes beyond that because epistemology and epistemological beliefs can affect learning and perception of learning or as a learner.

What is Epistemology?

Epistemology, as a branch of philosophy, has a rich and varied history, serving as a cornerstone of philosophical inquiry since the era of ancient Greece. It is a study that grapples with profound questions concerning the very essence of knowledge and belief, examining the sources of knowledge, degrees of belief, and the complex interplay between true belief and justified belief. These questions are not just abstract musings but have practical implications for how we approach learning and teaching.

The Regress Argument and Scepticism

The history of epistemology is marked by debates and theories that seek to untangle the intricacies of knowledge. One such debate revolves around the regress argument, a cornerstone of sceptical arguments that question whether knowledge, as we understand it, is even attainable. This argument, which dates back to ancient philosophical discussions, has maintained a central position in modern philosophy, shaping our understanding of propositional knowledge and informing a variety of logical arguments. As we are stood on the precipice of AI powered pedagogy, we are still debating what learning is, what knowledge is and whether AI can help support students to understand how to learn as well as the curriculum content.

In essence, the regress argument posits that any proposition requires justification, and that justification in turn requires another justification, leading to an infinite regress. This challenges the very possibility of certain knowledge and has profound implications for how we think about learning and belief.

The Role of Epistemological Beliefs in Learning

Epistemological beliefs are individuals' beliefs about the nature of knowledge and learning. These beliefs play a crucial role in how students approach learning tasks, process information, and solve problems. Schommer-Aikins (2004) introduced the Embedded Systemic Model, which posits that epistemological beliefs are part of a broader, interconnected system that influences learning and problem-solving.

Types of Epistemological Beliefs

Simple Knowledge vs. Complex Knowledge: Beliefs about whether knowledge is simple and straightforward or complex and nuanced.

Certain Knowledge vs. Tentative Knowledge: Beliefs about whether knowledge is certain and unchanging or tentative and evolving.

Innate Ability vs. Acquired Ability: Beliefs about whether the ability to learn is an innate trait or can be developed through effort and experience.

Quick Learning vs. Gradual Learning: Beliefs about whether learning occurs quickly or gradually over time.

Research by Qian and Alvermann (1995) highlighted the impact of these beliefs on students' learning, particularly in science. They found that beliefs in simple and certain knowledge were associated with difficulties in understanding complex scientific concepts, while beliefs in gradual learning and the potential for acquired ability were linked to better conceptual understanding and application reasoning.

Impact on Academic Performance

Cano (2005), Anshori and Sastromiharjo (2023), and Noroozi (2023), found that epistemological beliefs significantly influence students' approaches to learning and their academic performance. Students who viewed knowledge as complex and evolving and who believed in their ability to learn through effort were more likely to adopt deep learning strategies and perform better academically.

Learned Helplessness and Epistemological Beliefs

Learned Helplessness, a concept introduced by Seligman (1972), refers to a state where individuals believe they have no control over the outcomes of their actions and therefore give up trying. Qian and Alvermann (1995) explored the relationship between epistemological beliefs and Learned Helplessness in secondary school students learning science concepts. They found that students with naive epistemological beliefs—such as viewing knowledge as simple and certain—were more likely to experience Learned Helplessness, especially when confronted with challenging learning tasks. Seyri and Rezaee, (2024) found that the emotional state and epistemological beliefs associated with Learned Helplessness led to much poorer academic performance.

Relating to Dweck's Mindsets

Carol Dweck's theory of fixed and growth mindsets closely aligns with the discussion of epistemological beliefs. Dweck posits that individuals with a fixed mindset believe that their abilities and intelligence are static and unchangeable, akin to those who view knowledge as simple and certain. In contrast, individuals with a growth mindset believe that their abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work, paralleling the beliefs in complex knowledge and acquired ability.

What Can Be Learned from Growth Mindset Controversies?

Recent research by Yeager and Dweck (2020) explores the controversies surrounding the growth mindset. They address questions about whether a growth mindset predicts student outcomes, the effectiveness and reliability of growth mindset interventions, and the significance of effect sizes. Their findings confirm that growth mindset effects are replicable and meaningful, though they vary across individuals and contexts. They emphasise the importance of standardised measures and interventions, and the need to understand where and why growth mindset interventions may not work (Yeager & Dweck, 2020).

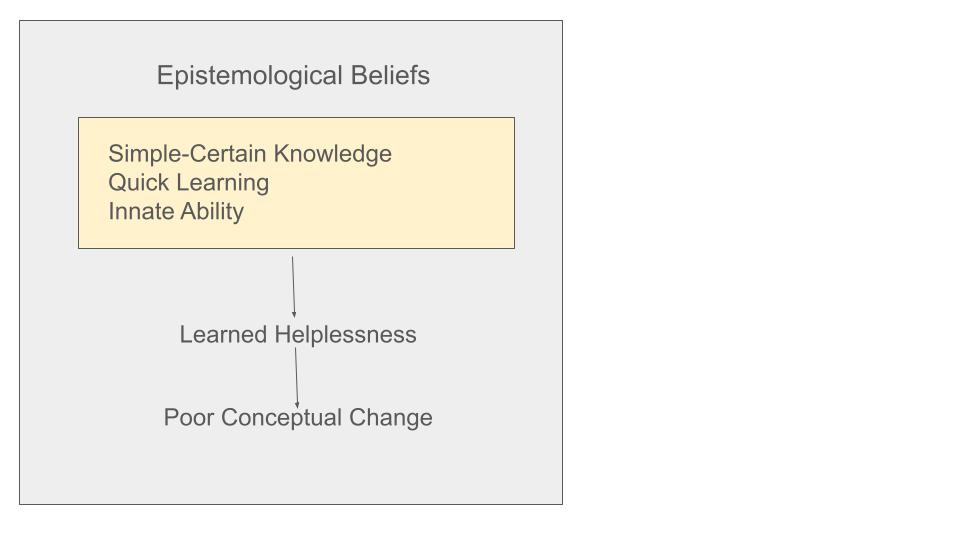

Diagram 1: Interaction of Epistemological Beliefs and Learned Helplessness

Students who believe that knowledge is simple and certain, and that learning should be quick and effortless, are more likely to give up when faced with difficult concepts. In contrast, those who see knowledge as complex and learning as a gradual process are more resilient and better equipped to handle academic challenges.

Fostering Learner Autonomy through Generative AI

Learner autonomy is the ability of learners to take charge of their own learning. Thanasoulas (2000) emphasises that autonomy involves developing the capacity for detachment, critical reflection, decision-making, and independent action. In today's digital age, Generative AI can play a pivotal role in supporting and enhancing learner autonomy. However, it would seem logical that epistomoloigcal beliefs would also influence how students use AI to support learning: some students will use AI to support their depth and breadth of learning, whereas others will need much more support in order to do that.

How Generative AI Supports Learner Autonomy

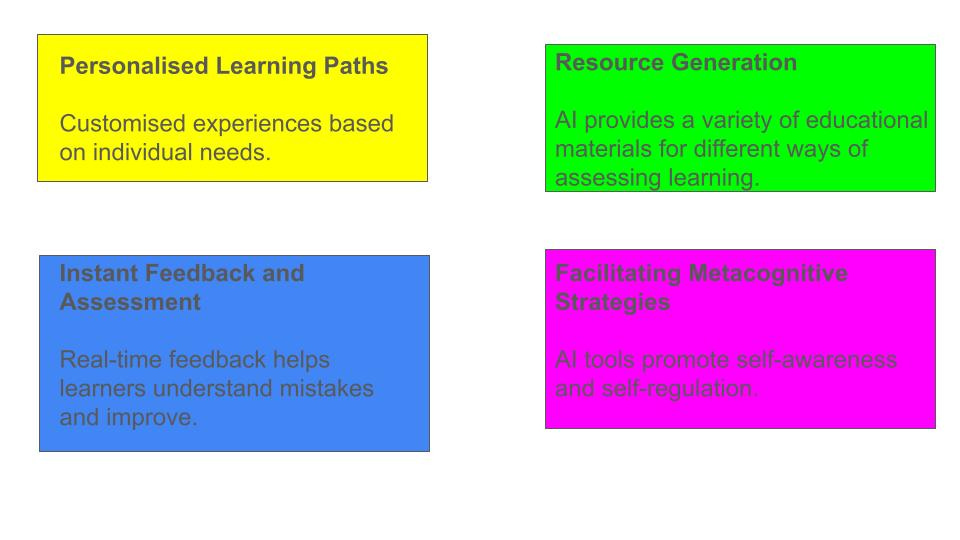

Personalised Learning Paths: AI can analyse students' learning styles, strengths, and weaknesses to create customised learning plans. This personalisation helps students engage with the material in a way that suits them best, promoting a deeper understanding and greater independence.

Instant Feedback and Assessment: AI-driven tools provide real-time feedback on assignments and assessments, allowing students to learn from their mistakes and understand concepts more clearly. This immediate feedback loop is essential for autonomous learning as it encourages self-correction and continuous improvement.

Resource Generation: AI can generate a wide range of learning resources, such as practice problems, study guides, and interactive simulations. These resources can be tailored to individual learning needs, providing students with the tools they need to explore topics independently.

Facilitating Metacognitive Strategies: AI tools can help students develop metacognitive strategies, such as planning, monitoring, and evaluating their own learning. By promoting self-awareness and self-regulation, these tools empower students to take control of their educational journey.

Diagram 2: AI and Learner Autonomy

By leveraging the capabilities of Generative AI, educators can create a learning environment that fosters independence and resilience. AI-driven tools support students in becoming active participants in their own learning process, equipping them with the skills necessary to navigate the complexities of knowledge acquisition.

Final Thoughts

Epistemology provides a critical framework for understanding how knowledge is acquired and validated. Epistemological beliefs significantly influence how students approach learning, process information, and respond to challenges. By addressing these beliefs and leveraging the power of Generative AI, educators can support the development of autonomous, resilient learners who believe in themselves as learners.

Incorporating AI into the educational landscape offers numerous benefits, from personalised learning experiences to real-time feedback and resource generation. As we continue to explore the potential of AI in education, it is essential to focus on empowering students to take charge of their own learning, fostering an environment of critical thinking and lifelong learning.

References

Anshori, D. and Sastromiharjo, A., 2023. Effectiveness of Epistemic Beliefs and Scientific Argument to Improve Learning Process Quality. International Journal of Instruction, 16(2).

Cano, F., 2005. Epistemological beliefs and approaches to learning: Their change through secondary school and their influence on academic performance. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 75(2), pp.203-221.

Noroozi, O., 2023. The role of students’ epistemic beliefs for their argumentation performance in higher education. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 60(4), pp.501-512.

Qian, G., & Alvermann, D., 1995. Role of epistemological beliefs and learned helplessness in secondary school students' learning science concepts from text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(2), pp.282-292.

Schommer-Aikins, M., 2004. Explaining the epistemological belief system: Introducing the embedded systemic model and coordinated research approach. Educational Psychologist, 39(1), pp.19-29.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1972). Learned Helplessness. Annual Review of Medicine, 23(1), 407-412. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.me.23.020172.002203

Seyri, H. and Rezaee, A.A., 2024. An autonomy-oriented response to EAP students’ learned helplessness in online classes. Current Psychology, 43(9), pp.7887-7898.

Thanasoulas, D., 2000. Autonomy and learning: An epistemological approach. Applied Semiotics, 10, pp.115-131.

Yeager, D.S. and Dweck, C.S., 2020. What can be learned from growth mindset controversies?. American Psychologist, 75(9), p.1269.